A Survey on Multimodal Large Language Models

A Survey on Multimodal Large Language Models

A typical MLLM can be abstracted into three modules

- a pre-trained modality encoder

- a pre-trained LLM

- a modality interface to connect them (connector)

There are broadly three types of connectors.

Token level

- projection-based

- query-based

Feature level

- fusion-based

Modality encoder

Rather than training from scratch, a common approach is to use a pretrained encoder that has been aligned to other modalities. For example, CLIP [13] incorporates a visual encoder semantically aligned with the text through large-scale pretraining on image-text pairs. Therefore, it is easier to use such initially pre-aligned encoders to align with LLMs through alignment pre-training

Pre-trained LLM

Instead of training an LLM from scratch, it is more efficient and practical to start with a pre-trained one. Through tremendous pre-training on web corpus, LLMs have been embedded with rich world knowledge, and demonstrate strong generalization and reasoning capabilities.

Modality interface

However, it would be costly to train a large multimodal model in an end-to-end manner.

A more practical way is to introduce a learnable connector between the pre-trained visual encoder and LLM.

token level fusion

For token-level fusion, features output from encoders are transformed into tokens and concatenated with text tokens before being sent into LLMs. A common and feasible solution is to leverage a group of learnable query tokens to extract information in a query-based manner [69], which first has been implemented in BLIP-2 [59], and subsequently inherited by a variety of work [26], [60], [70]. Such Q-Formerstyle approaches compress visual tokens into a smaller number of representation vectors.

In contrast, some methods simply use a MLP-based interface to bridge the modality gap [20], [37], [71], [72]. For example, LLaVA series adopts one/two linear MLP [20], [50] to project visual tokens and align the feature dimension with word embeddings.

On a related note, MM1 [52] has ablated on design choices on the connector and found that for token-level fusion, the type of modality adapter is far less important than the number of visual tokens and input resolution. Nevertheless, Zeng et al. [73] compare the performance of token and feature-level fusion, and empirically reveal that the token-level fusion variant performs better in terms of VQA benchmarks. Regarding the performance gap, the authors suggest that cross-attention models might require a more complicated hyper-parameter searching process to achieve comparable performance.

feature level fusion

As another line, feature-level fusion inserts extra modules that enable deep interaction and fusion between text features and visual features. For example, Flamingo [74] inserts extra cross-attention layers between frozen Transformer layers of LLMs, thereby augmenting language features with external visual cues. Similarly, CogVLM [75] plugs in a visual expert module in each Transformer layer to enable dual interaction and fusion between vision and language features. For better performance, the QKV weight matrix of the introduced module is initialized from the pre-trained LLM. Similarly, LLaMA-Adapter [76] introduces learnable prompts into Transformer layers. These prompts are first embedded with visual knowledge and then concatenated with text features as prefixes.

The other approach is to translate images into languages with the help of expert models, and then send the language to LLM.

expert models

Apart from the learnable interface, using expert models, such as an image captioning model, is also a feasible way to bridge the modality gap [77], [78], [79], [80].

Pre-training

As illustrated in Table 3, given an image, the model is trained to predict autoregressively the caption of the image, following a standard cross-entropy loss.

A common approach for pre-training is to keep pre-trained modules (e.g. visual encoders and LLMs) frozen and train a learnable interface [20], [35], [72]. The idea is to align different modalities without losing pre-trained knowledge. Some methods [34], [81], [82] also unfreeze more modules (e.g. visual encoder) to enable more trainable parameters for alignment.

For short and noisy caption data, a lower resolution (e.g. 224) can be adopted to speed up the training process, while for longer and cleaner data, it is better to utilize higher resolutions (e.g. 448 or higher) to mitigate hallucinations. Besides, ShareGPT4V [83] finds that with high-quality caption data in the pretraining stage, unlocking the vision encode promotes better alignment.

Data

Coarse-grained

These data can be cleaned and filtered via automatic tools, for example, using CLIP [13] model to filter out imagetext pairs whose similarities are lower than a pre-defined threshold.

some representative coarse-grained datasets: CC, SBU, LAION, COYO-700M

fine-grained

Recently, more works [83], [91], [92] have explored generating high-quality fine-grained data through prompting strong MLLMs (e.g. GPT-4V). Compared with coarsegrained data, these data generally contain longer and more accurate descriptions of the images, thus enabling finergrained alignment between image and text modalities. However, since this approach generally requires calling commercial-use MLLMs, the cost is higher, and the data volume is relatively smaller.

Instruction-tuning

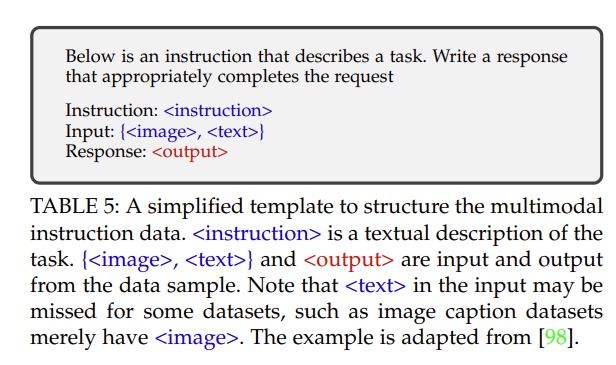

A multimodal instruction sample often includes an optional instruction and an input-output pair. The instruction is typically a natural language sentence describing the task, such as, “Describe the image in detail.” The input can be an image-text pair like the VQA task [99] or only an image like the image caption task [100]. The output is the answer to the instruction conditioned on the input. The instruction template is flexible and subject to manual designs [20], [25], [98], as exemplified in Table 5. Note that the instruction template can also be generalized to the case of multi-round conversations [20], [37], [71], [98].

Data collection

Data Adaptation

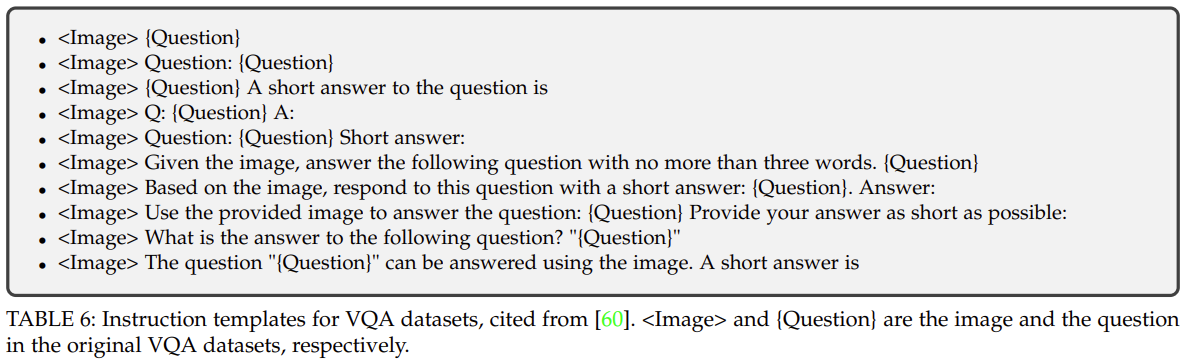

Take the transformation of VQA datasets for an example, the original sample is an input-out pair where the input comprises an image and a natural language question, and the output is the textual answer to the question conditioned on the image. The input-output pairs of these datasets could naturally comprise the multimodal input and response of the instruction sample.

The instructions, i.e. the descriptions of the tasks, can either derive from manual design or from semi-automatic generation aided by GPT.

Note that since the answers of existing VQA and caption datasets are usually concise, directly using these datasets for instruction tuning may limit the output length of MLLMs.

Stategies:

- specify explicitly in instructions. For example, ChatBridge [104] explicitly declares short and brief for shortanswer data, as well as a sentence and single sentence for conventional coarse-grained caption data

- extend the length of existing answers [105]. For example, M3 IT [105] proposes to rephrase the original answer by prompting ChatGPT with the original question, answer, and contextual information of the image (e.g. caption and OCR).

Self-Instruction

some works collect samples through self-instruction [106], which utilizes LLMs to generate textual instruction-following data using a few hand-annotated samples.

LLaVA [20] extends the approach to the multimodal field by translating images into text of captions and bounding boxes, and prompting text-only GPT-4 to generate new data with the guidance of requirements and demonstrations. In this way, a multimodal instruction dataset is constructed, called LLaVA-Instruct-150k.

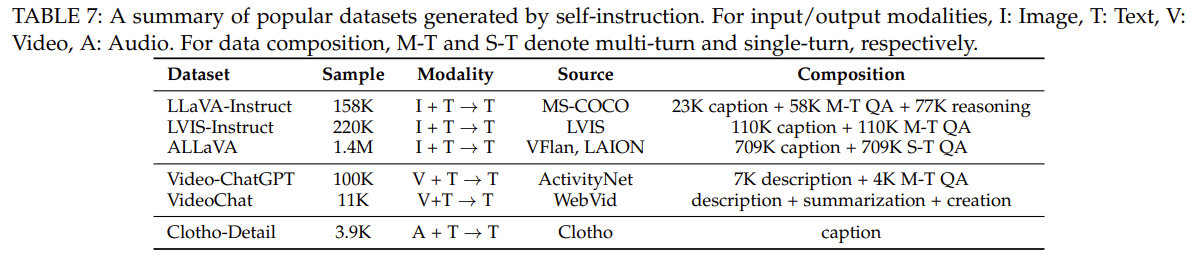

Recently, with the release of the more powerful multimodal model GPT4V, many works have adopted GPT-4V to generate data of higher quality, as exemplified by LVIS-Instruct4V [91] and ALLaVA [92]. We summarize the popular datasets generated through self-instruction in Table 7.

Data Mixture

Apart from the multimodal instruction data, language-only user-assistant conversation data can also be used to improve conversational proficiencies and instruction-following abilities. LaVIN [101] directly constructs a minibatch by randomly sampling from both language-only and multimodal data. MultiInstruct [102] probes different strategies for training with a fusion of single modal and multimodal data, including mixed instruction tuning (combine both types of data and randomly shuffle) and sequential instruction tuning (text data followed by multimodal data).

Data Quality

Recent research has revealed that the data quality of instruction-tuning samples is no less important than quantity. Lynx [73] finds that models pre-trained on large-scale but noisy image-text pairs do not perform as well as models pre-trained with smaller but cleaner datasets. Similarly, Wei et al. [108] finds that less instruction-tuning data with higher quality can achieve better performance.

For data filtering, the work proposes some metrics to evaluate data quality and, correspondingly, a method to automatically filter out inferior vision-language data. Here we discuss two important aspects regarding data quality.

- Prompt Diversity. The diversity of instructions has been found to be critical for model performance. Lynx [73] empirically verifies that diverse prompts help improve model performance and generalization ability.

- Task Coverage. In terms of tasks involved in training data, Du et al. [109] perform an empirical study and find that the visual reasoning task is superior to captioning and QA tasks for boosting model performance. Moreover, the study suggests that enhancing the complexity of instructions might be more beneficial than increasing task diversity and incorporating fine-grained spatial annotations.

Alignment tuning

Alignment tuning is more often used in scenarios where models need to be aligned with specific human preferences. Currently, Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF) and Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) are two main techniques for alignment tuning.

RLHF

This technique aims to utilize reinforcement learning algorithms to align LLMs with human preferences, with human annotations as supervision in the training loop. As exemplified in InstructGPT [95], RLHF incorporates three key steps:

Supervised fine-tunning. This step aims to fine-tune a pre-trained model to present the preliminary desired output behavior. The fine-tuned model in the RLHF setting is called a policy model. Note that this step might be skipped since the supervised policy model π SFT can be initialized from an instruction-tuned model

Reward modeling. A reward model is trained using preference pairs in this step. Given a multimodal prompt (e.g. image and text) \(x\) and a response pair \(\left(y_w, y_l\right)\), the reward model \(r_\theta\) learns to give a higher reward to the preferred response \(y_w\), and vice versa for \(y_l\), according to the following objective: \[ \mathcal{L}(\theta)=-\mathbb{E}_{\left(x, y_w, y_l\right) \sim \mathcal{D}}\left[\operatorname { l o g } \left(\sigma\left(r_\theta\left(x, y_w\right)-r_\theta\left(x, y_l\right)\right]\right.\right. \]

Reinforcement learning. In this step, the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm is adopted to optimize the RL policy model \(\pi_\phi^{\mathrm{RL}}\). A per-token KL penalty is often added to the training objective to avoid deviating too far from the original policy [95], resulting in the objective: \[ \begin{aligned} \mathcal{L}(\phi) & =-\mathbb{E}_{x \sim \mathcal{D}, y \sim \pi_\phi^{R L}(y \mid x)}\left[r_\theta(x, y)\right. \\ & \left.-\beta \cdot \mathbb{D}_{K L}\left(\pi_\phi^{R L}(y \mid x) \| \pi^{R E F}(y \mid x)\right)\right] \end{aligned} \]

where \(\beta\) is the coefficient for the KL penalty term. Typically, both the RL policy \(\pi_\phi^{\mathrm{RL}}\) and the reference model \(\pi^{\mathrm{REF}}\) are initialized from the supervised model \(\pi^{\mathrm{SFT}}\). The obtained RL policy model is expected to align with human preferences through this tuning process.

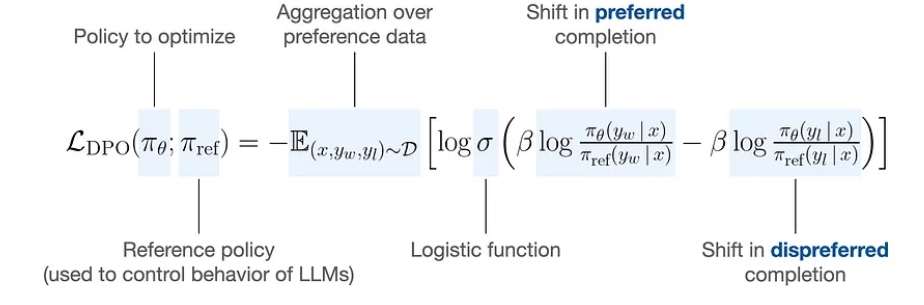

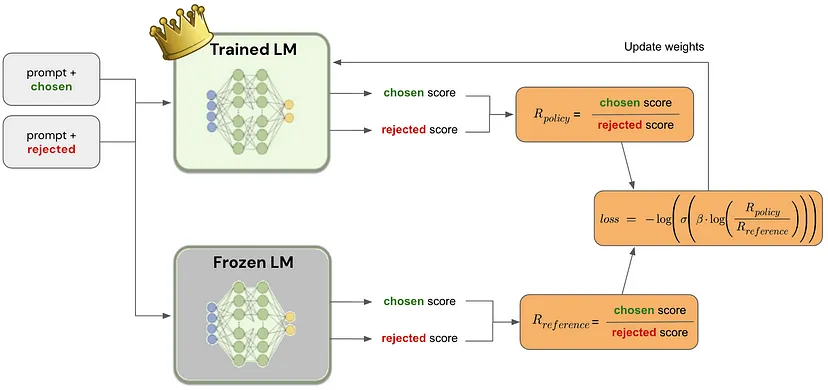

DPO

It learns from human preference labels utilizing a simple binary classification loss. Compared with the PPO based RLHF algorithm, DPO is exempt from learning an explicit reward model, thus simplifying the whole pipeline to two steps, i.e. human preference data collection and preference learning. The learning objective is as follows: \[ \begin{aligned} \mathcal{L}(\phi) & =-\mathbb{E}_{\left(x, y_w, y_l\right) \sim \mathcal{D}}\left[\operatorname { l o g } \sigma \left(\beta \log \frac{\pi_\phi^{\mathrm{RL}}\left(y_w \mid x\right)}{\pi^{\mathrm{REF}}\left(y_w \mid x\right)}\right.\right. \left.\left.-\beta \log \frac{\pi_\phi^{\mathrm{RL}}\left(y_l \mid x\right)}{\pi^{\mathrm{REF}}\left(y_l \mid x\right)}\right)\right] \end{aligned} \]

Data

The gist of data collection for alignment-tuning is to collect feedback for model responses, i.e. to decide which response is better. It is generally more expensive to collect such data, and the amount of data used for this phase is typically even less than that used in previous stages. In this part, we introduce some datasets and summarize them in Table 8.

- LLaVA-RLHF [112]. It contains 10 K preference pairs collected from human feedback in terms of honesty and helpfulness. The dataset mainly serves to reduce hallucinations in model responses.

- RLHF-V [114]. It has 5.7 K fine-grained human feedback data collected by segment-level hallucination corrections.

- VLFeedback [115]. It utilizes AI to provide feedback on model responses. The dataset contains more than 380 K comparison pairs scored by GPT- 4 V in terms of helpfulness, faithfulness, and ethical concerns.