ACE

Abstract

Most existing foundational diffusion models are primarily designed for text-guided visual generation and do not support multi-modal conditions, which are essential for many visual editing tasks. In this work, we propose ACE, an All-round Creator and Editor, which achieves comparable performance compared to those expert models in a wide range of visual generation tasks.

To achieve this goal, we first introduce a unified condition format termed Long-context Condition Unit (LCU), and propose a novel Transformer-based diffusion model that uses LCU as input, aiming for joint training across various generation and editing tasks. Furthermore, we propose an efficient data collection approach to address the issue of the absence of available training data.

Introduction

LLM like ChatGPT, such unified architecture has not been fully explored in visual generation field. Existing foundational models of visual generation typically create images or videos from pure text, which is not compatible with most visual generation tasks, such as controllable image generation or image editing. To address this, we design a unified framework using a Diffusion Transformer generation model that accommodates a wide range of inputs and tasks, empowering it to serve as an All-round Creator and Editor, which we refer to as ACE.

define Condition Unit (CU), which establishes a unified input paradigm consisting of core elements such as image, mask, and textual instruction

for those CUs containing multiple images, we introduce Image Indicator Embedding to ensure the order of the images mentioned in instruction matches image sequence within the CUs. we imply 3d position embedding instead of 2d spatial-level position embedding on the image sequence, allowing for better exploring the relationships among conditional images

Third, we concatenate the current CU with historical information from previous generation rounds to construct the Long-context Condition Unit (LCU). By leveraging this chain of generation information, we expect the model to better understand the user’s request and create the desired image.

Data Collection:

To address the issue of the absence of available training data for various visual generation tasks, we establish a meticulous data collection and processing workflow to collect high-quality structured CU data at a scale of 0.7 billion. For visual conditions, we collect image pairs by synthesizing images from source images or by pairing images from large-scale databases. The former utilizes powerful open-source models to edit images to meet specific requirements, such as changing styles (Han et al., 2024) or adding objects (Pan et al., 2024), while the latter involves clustering and grouping images from extensive databases to provide sufficient real data, thereby minimizing the risk of overfitting to the synthesized data distribution. For textual instructions, we first manually construct instructions for diverse tasks by building templates or requesting LLMs, then optimize the instruction construction process by training an end-to-end instruction-labeling multi-modal large language model (MLLM) (Chen et al., 2024), thereby enriching the diversity of the text instructions.

ACE

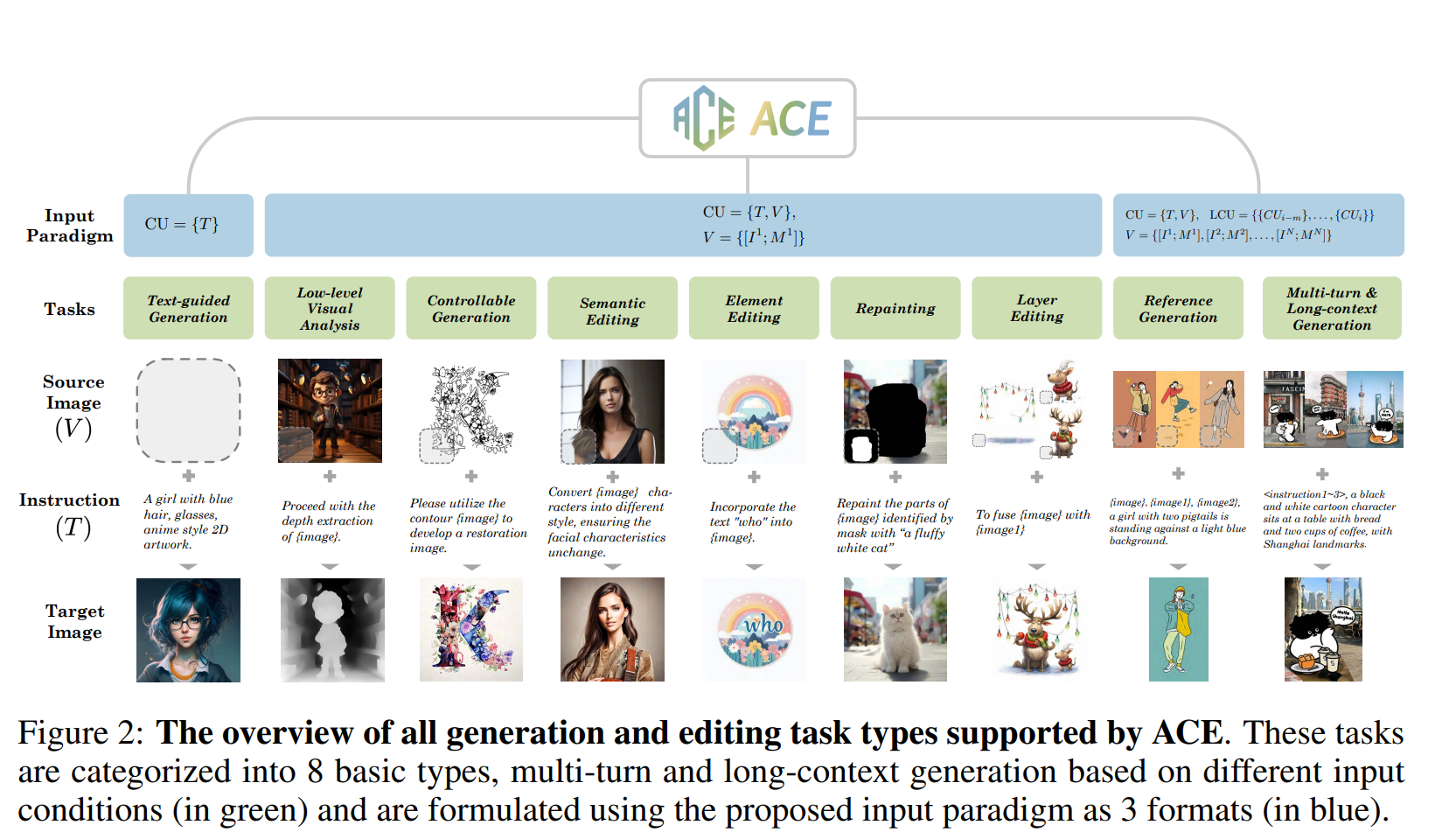

Tasks

- Textual modality

- Generation-based Instructions

- Editing-based Instructions

- Visual modality

- Text-guided Generation: only uses generating-based text prompt

- Low-level Visual Analysis: extracts low-level visual features from input images, such as edge maps or segmentation maps. One source image and editing-based instruction are required in the task to accomplish creation.

- Controllable Generation: It is the inverse task of Low-level Visual Analysis

- Semantic Editing: It aims to modify some semantic attributes of an input image by providing editing instructions, such as altering the style of an image or modifying the facial attributes of a character.

- Element Editing: It focuses on adding, deleting, or replacing a specific subject in the image while keeping other elements unchanged.

- Repainting: It erases and repaints partial image content of input image indicated by given mask and instruction.

- Layer Editing: It decomposes an input image into different layers, each of which contains a subject or background, or reversely fuses different layers.

- Reference Generation: It generates an image based on one or more reference images, analyzing the common elements among them and presenting these elements in the generated image.

Input paradigm

\[ \mathrm{CU}=\{T, V\}, \quad V=\left\{\left[I^1 ; M^1\right],\left[I^2 ; M^2\right], \ldots,\left[I^N ; M^N\right]\right\}, \]

where a channel-wise connection operation is performed between corresponding \(I\) and \(M, N\) represents the total number of visual information inputs for this task.

Furthermore, to better address the demands of complex long-context generation and editing, historical information can be optionally integrated into CU, which is formulated as: \[ \mathbf{L C U}_i=\left\{\left\{T_{i-m}, T_{i-m+1}, \ldots, T_i\right\},\left\{V_{i-m}, V_{i-m+1}, \ldots, V_i\right\}\right\} \] where \(m\) denotes the maximum number of rounds of historical knowledge introduced in the current request. \(\mathrm{LCU}_i\) is a Long-context Condition Unit used to generate desired content for the \(i\)-th request.

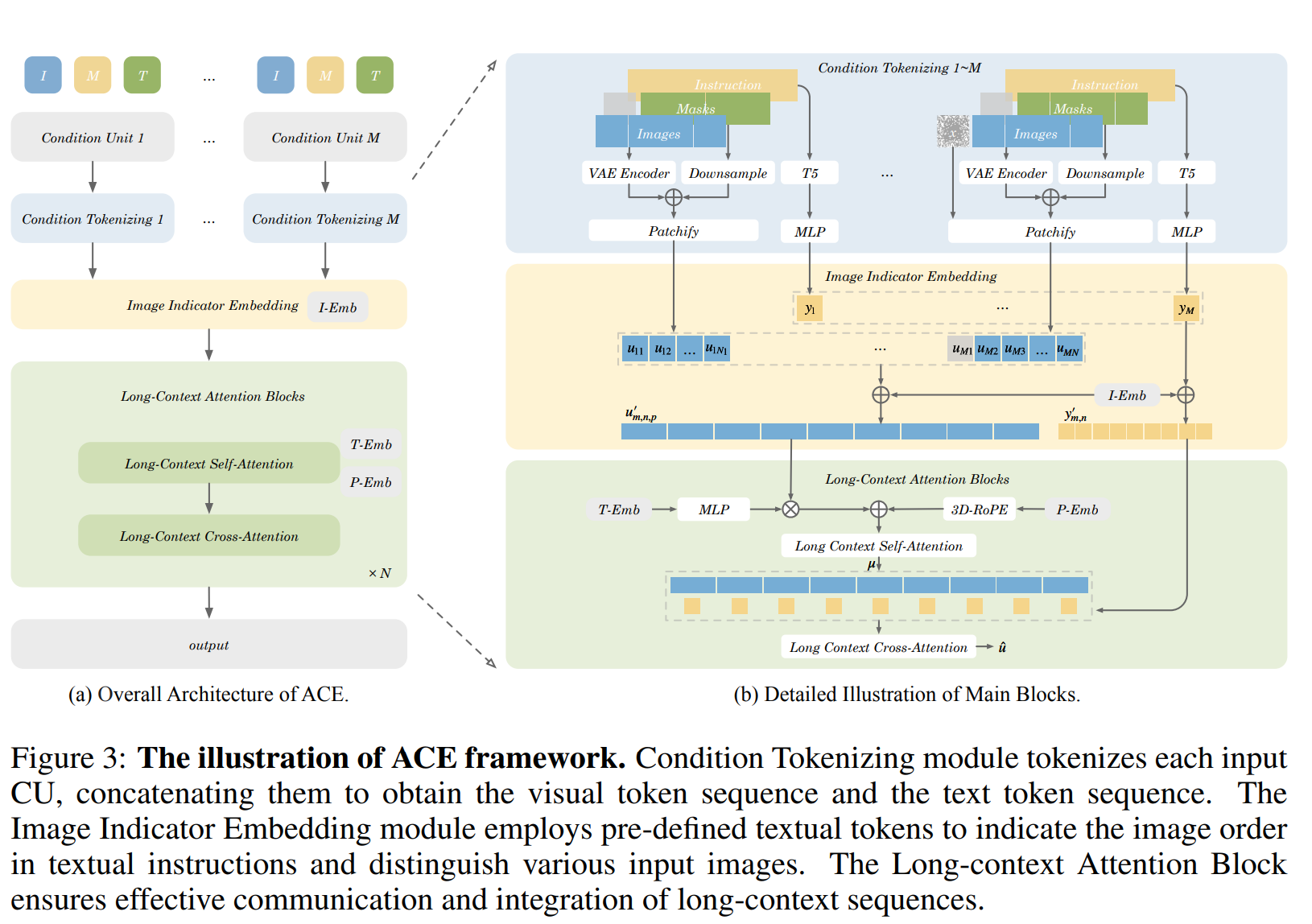

Architecture

the overall framework is built based on a Diffusion Transformer model (Scalable Diffusion Models with Transformers) , and integrated with three novel components to achieve unified generation:

Condition Tokenizing

Considering an LCU that comprises \(M\) CUs, the model involves three entry points for each CU:

- a language model (T5) (Raffel et al., 2020) to encode textual instructions,

- a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) (Kingma & Welling, 2014) to compress reference image to latent representation,

- a down-sampling module to resize mask to the shape of corresponding latent image.

The latent image and its mask (an all-one mask if no mask is provided) are concatenated along the channel dimension.

These image-mask pairs are then patchified into 1-dimensional visual token sequences \(u_{m, n, p}\), where \(m, n\) are indexes for CUs and visual information Vs in each CU, while \(p\) denotes the spatial index in patchified latent images. Similarly, textual instructions are encoded into 1 -dimensional token sequences \(y_m\).

After processing within each CU, we separately concatenate all visual token sequences and all textual token sequences to form a long-context sequence.

Image Indicator Embedding

my understanding: add textual {Image N} embedding to each image-mask pair sequence \(u_{m,n,p}\) and corresponding text embedding \(T_{m}\).

As illustrated as Fig. 3b, to indicate the image order in textual instructions and distinguish various input images, we encode some pre-defined textual tokens "{image \(\},\{\) image 1\(\}, \ldots,\{\) imageN \(\} "\) into T5 embeddings as Image Indicator Embeddings (I-Emb). These indicator embeddings are added to the corresponding image embedding sequence and text embedding sequence, which is formulated as:

\[ \begin{gathered} y_{m, n}^{\prime}=y_m+I-\operatorname{Emb}_{m, n} \\ u_{m, n, p}^{\prime}=u_{m, n, p}+I-\operatorname{Emb}_{m, n} \end{gathered} \]

In this way, image indicator tokens in textual instructions and the corresponding images are implicitly associated.

Long-context Attention Block

Given the long-context visual sequence, we first modulate it with the time step embedding ( \(T\)-Emb), then incorporate a 3D Rotational Positional Encodings (RoPE) (Su et al., 2023) to differentiate between different spatial and frame-level image embeddings.

During the Long Context Self-Attention, all image embeddings of each CU at each spatial location, are equivalently and comprehensively interact with each other by \(\mu=\operatorname{Attn}\left(u^{\prime}, u^{\prime}\right)\). Next, unlike the cross-attention layer of the conventional Diffusion Transformer model, where each visual token attends to all of the textual tokens, we implement cross-attention operation with each condition unit. That means image tokens in \(m\)-th CU will only attend to the textual tokens from the same CU. This can be formulated as: \[ \hat{u}_{m, n}=\operatorname{Attn}\left(\mu_{m, n}, y_{m, n}^{\prime}\right) . \] This ensures that, within the cross-attention layer, the text embeddings and image embeddings align on a frame-by-frame basis.

Datasets

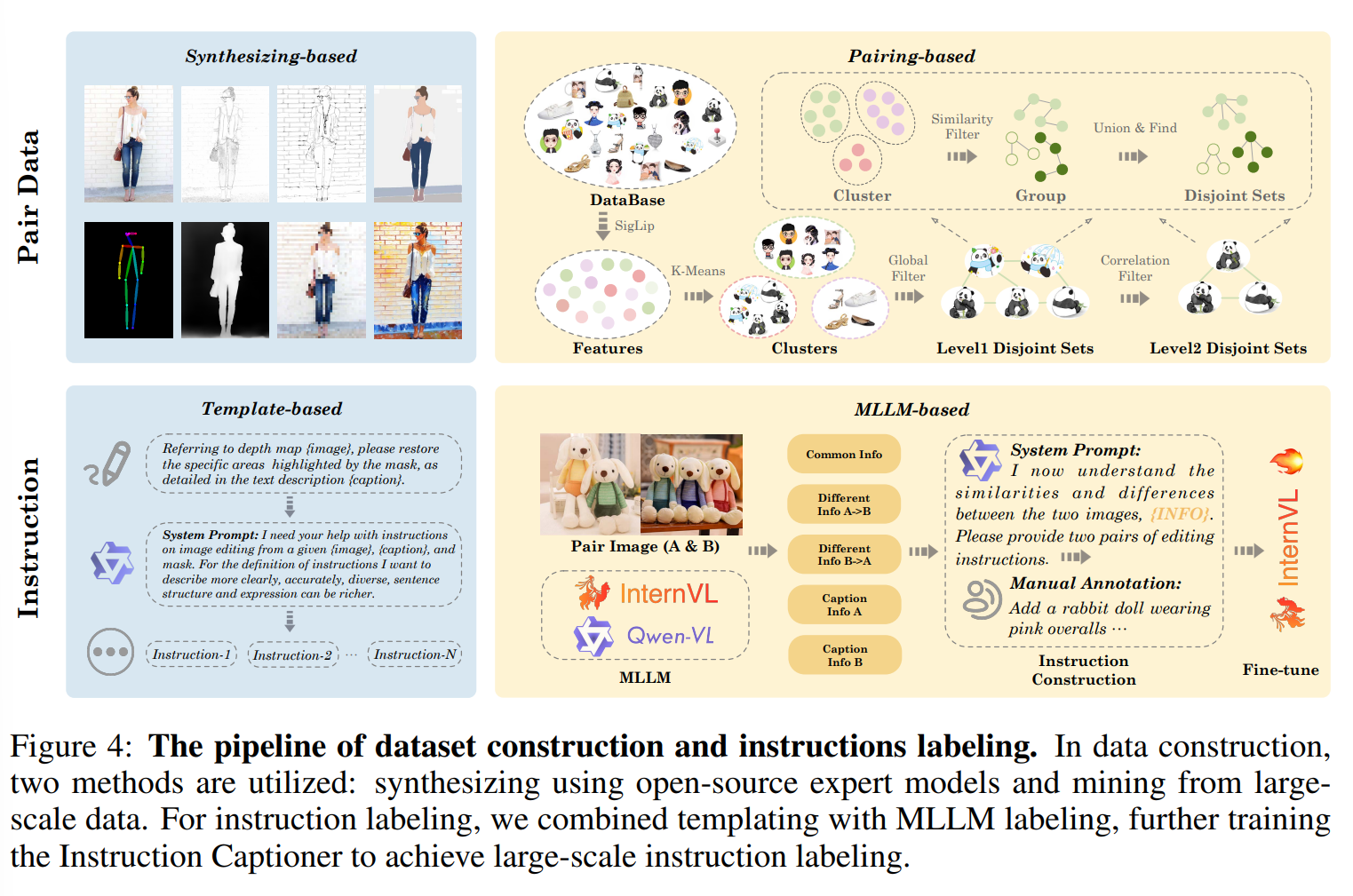

pair data collection

Synthesizing from source image

Pairing from massive databases

We first extract semantic features using SigLIP (Zhai et al., 2023) from large-scale datasets (e.g., LAION-5B (Schuhmann et al., 2022), OpenImages (OpenImage, 2023), and our private datasets). Then leveraging K-means clustering technology, coarse-grained clustering is implemented to divide all images into tens of thousands of clusters. Within each cluster, we implement a two-turn union-find algorithm to achieve fine-grained image aggregation. The first turn is based on the SigLIP feature and the second turn uses a similarity score tailored for specific tasks. For instance, we calculate the face similarity score for the facial editing task and the object consistency score for the general editing task. Finally, we collect all possible pairs from each disjoint set and implement cleaning strategies to filter high-quality pairs. Benefiting from these two automatic pipelines, we construct a large-scale training dataset that consists of nearly 0.7 billion image pairs, covering 8 basic types of tasks, multi-turn and long-context generation. We depict its distribution in Fig. 6 and provide a detailed description of the specific data construction methods for each task, please refer to appendix B.

Instructions

- Template based

- MLLM-based

For tasks that contain non-natural images, we utilize a template-based method to generate instruction templates. These templates are then combined with the generated captions to produce the final instructions. To address the issue of insufficient diversity, we employ LLMs to reformulate instructions multiple times, and tune prompts to ensure that each rewritten version is distinct from all preceding instructions.

For tasks that contain natural images, we employ an MLLM to predict the differences and commonalities between the images in the input pair. Then an LLM is used to generate instructions focusing on semantic distinctions according to the analysis of the differences and commonalities. Further, the collected instructions generated by these two methods undergo human annotation and correction. The revised instructions are used for fine-tuning an open-source MLLM, enabling it to predict instructions for any given image pair. Specifically, we collect a dataset of approximately 800,000 curated instructions and train an Instruction Captioner by fine-tuning the InternVL2-26B (Chen et al., 2024).